Here’s a fun fact: Modern crowdfunding was pioneered by a British progressive-rock band.

Yes, you read that correctly. Fundraising is canonically hardcore. In 1997, British band Marillion couldn’t front the $60,000 cost to do an eagerly requested reunion tour in the United States; the band sent out an email to its 1,000-person mailing list explaining the situation. The result? One fan volunteered to lead the charge and manage a bank account to collect donations for the band. Within weeks, Marillion had roughly $20,000 in fan contributions; the band eventually raised the full amount. Thus, crowdfunding as we know it today was born. The term “crowdfunding,” coined by the founder of the failed fundavlog venture Michael Sullivan, didn’t come around until 2006.

The rise of crowdfunding platforms

Marillion’s story inspired other bands to tap into their fan bases for financial support related to musical projects. In 2001, ArtistShare emerged as the first dedicated crowdfunding platform, geared specifically toward musicians raising money for an album or tour. Around the same time, JustGiving launched in the United Kingdom and has since raised over $5 billion for more than 29,000 charities in the past decade. From there, Kiva launched in 2005 and provided crowdfunded microloans to low-income entrepreneurs and students across the world. Crowdfunding platforms saw their true surge in popularity toward the end of the 2000s with the proliferation of giants like Indiegogo (2007), Kickstarter (2009), and GoFundMe (2010). There isn’t a specific moment that marks when nonprofits en masse started using these platforms for their fundraising, but the last five years have seen tremendous spike in nonprofit crowdfunding campaigns.

Globally, there are an estimated 600+ crowdfunding platforms that exist today; this doesn’t include the rising number of fundraising software that offer some peer-to-peer campaign building features either. There are now crowdfunding platforms specifically intended for use by nonprofits, too, including Mightycause, CrowdRise, and Panorama. Of the 226 fundraising products categorized on G2, 51 of them (22.6%) offer functionality to run a crowdfunding campaign. Crowdfunding has become a powerful fundraising tool for nonprofits, but only if nonprofits understand how to properly utilize the platform.

The power of crowdfunding

Statista predicts total global crowdfunding will increase 14.7% annually over the next four years. It’s easy to see why. Crowdfunding has fundamentally transformed how people fundraise for personal projects, events, debt and bills (withholding the criticisms for now), social causes, and even business ventures. People can rally a global community to crowdfund almost anything. Some examples include making potato salad, creating a new TLC album, and the recent Hurricane Harvey relief fund that raised $41.6 million—now it’s considered the world’s largest crowdsourced fundraiser.

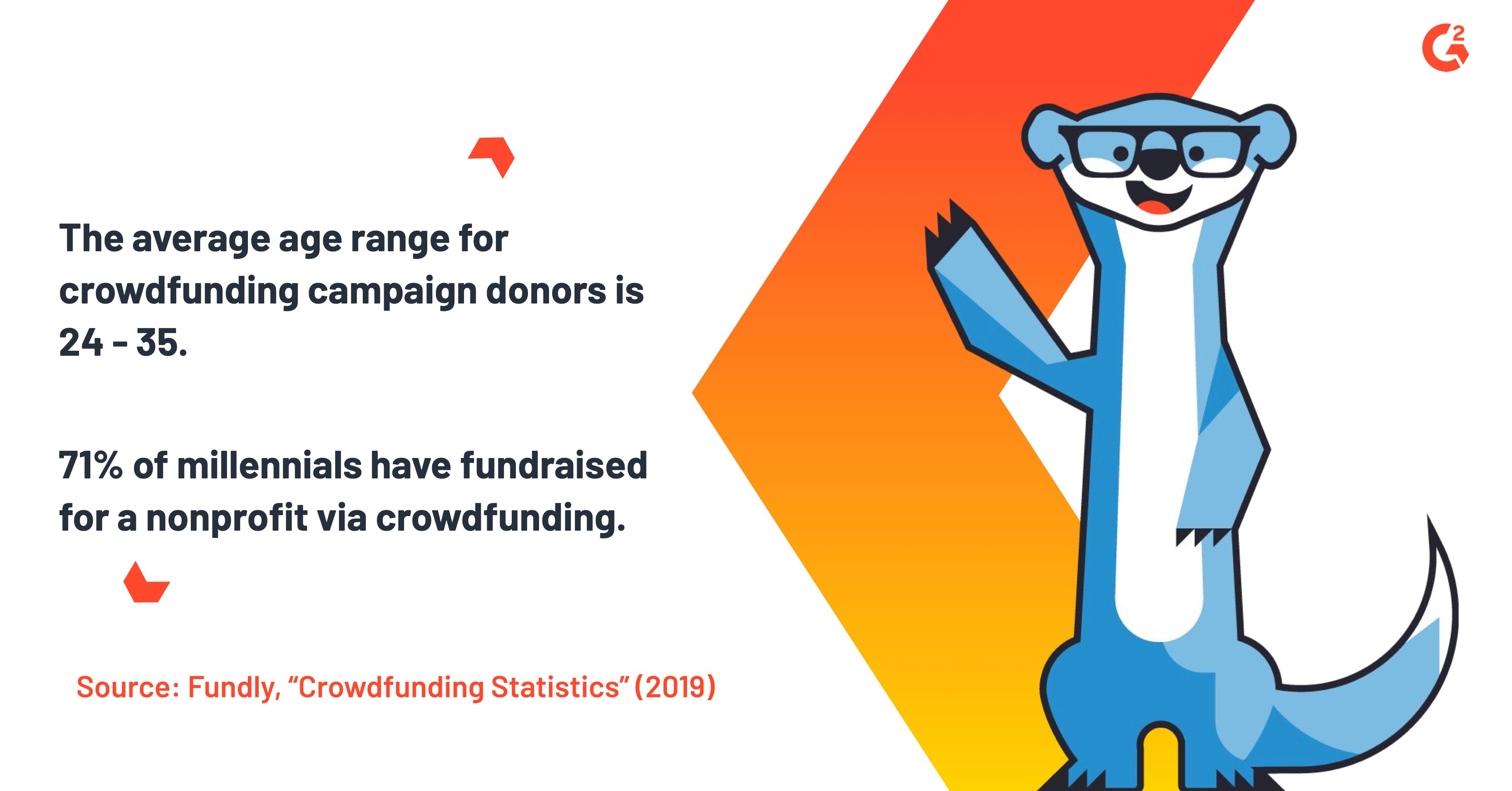

As nonprofits target more millennial donors, crowdfunding and similar digital fundraising platforms will become essential tools. Crowdfunding campaigns lean into the emotional aspect of social causes, presenting a quick, compelling narrative for why a project deserves to be funded. Much like G2 emphasizes the power of peer review, crowdfunding creates a platform for an individual to testify to the importance of a cause and persuade their social network to donate. Peer pressure works in fundraising; people are more likely to donate to a cause if their friend does (hello, birthday Facebook Fundraisers). There is a sense of FOMO (and perhaps guilt) watching other do-gooders offer financial support to an individual or organization and make a positive impact in the lives of others.

Furthermore, crowdfunding eliminates barriers to traditional fundraising, such as geographic location. Anyone can stumble on a nonprofit’s crowdfunding page, and the more social shares a crowdfunding page receives, the more likely it will appear on the timeline of charitable donors. Nonprofits leveraging these platforms spend time crafting a compelling message and cause. While capital campaigns for building renovations or equipment seem like the easiest route, nonprofits can create a campaign for seemingly anything. The key to success lies in building the emotional element of the campaign to encourage donors.

One-third of all GoFundMe campaigns are for medical bills. They immediately trigger human compassion, telling the story of an individual’s misfortune, often with photos and videos to prove the medical necessity exists, but more importantly to present a tangible recipient for empathy. Nonprofits that perform the best with crowdfunding know how to do the same with their campaigns. For example, a nonprofit that needs to fund after-school programming can use a photo of program participants as the campaign cover photo, and then incorporate personal details about the young people with their call to action. Campaigns that include media and personalized videos raise 105% more compared with those that don’t. Crowdfunding is conditioning nonprofits to utilize digital resources and think critically about how to appeal to the general public—that’s a good thing.

Quer aprender mais sobre Software sem fins lucrativos? Explore os produtos de Sem fins lucrativos.

The shortcomings of crowdfunding

Despite all the accomplishments crowdfunding has helped facilitate, there are some concerns about the practice as well. For example, some worry that crowdfunding has introduced a sense of sensationalism into fundraising. The more extreme a story is, the more likely it may go viral and reach or exceed its goal. There is an inundation of people and causes fighting for funding, with crowdfunding, the best storyteller wins. While peers are more likely to donate to a cause if a friend does, the sheer volume of fundraising campaigns these days can lead to donor fatigue. The average American supports 4.5 charities, and nowadays most donate to well-established, nationally reaching nonprofits. People are more likely to donate to a crowdfunding campaign for the Human Rights Campaign or Feeding America compared to one for a local nonprofit.

Fundly’s data shows that only 28% of donors to nonprofit crowdfunding campaigns are repeat donors. Nonprofits need to build thoughtful fundraising strategies where crowdfunding is one component of a larger ecosystem, otherwise they risk losing donors due to a lack of meaningful engagement. Nonprofits Source data shows that 62% of donors who give to crowdfunding campaigns are new to crowdfunding. Nonprofits should have a solid stewardship strategy in place to convert top funnel donors into meaningful supporters. Crowdfunding opens the door to a relationship between fundseeker and fundgiver, but it offers little in terms of meaningful engagement beyond a brief feel-good exchange.

Still, nonprofits would be remiss to disparage a crowdfunding campaign. When executed properly, the financial and social benefits are too good to ignore. Plus, they force nonprofits to assess their media strategy and make necessary changes to enhance their organizational pitch. Nevertheless, nonprofits shouldn’t chase a viral sensation or compromise their morals for the allure of extra exposure.

Dominick Duda

Dominick is a Senior Research Analyst at G2 specializing in nonprofit software, with other vertical industry coverage including healthcare, government, and hospitality. Prior to joining G2, he spent years in the nonprofit sector as a fundraiser and grant writer, and he is deeply invested in understanding how nonprofits can make better use of the technology available to them. In his free time, he enjoys video games, museums, and reading and writing poetry.