At its core, the health care industry is a service-oriented one; it always has been. Only recently, with the realization that patient experience significantly impacts practice reputation, hospitals and medical practices have taken strides to consider patient satisfaction and perspective when delivering care.

The biggest contribution to improving patient care has been direct feedback from patients themselves. For better or for worse, patients are empowered to comment on the quality of care they receive. For example, in the case of chronic care management, patients are no longer considered low priority due to low fee-for-service returns. However, feedback can also have its issues as patients are human beings who do not necessarily understand the implications of health care operations or the intricacies of the health care system.

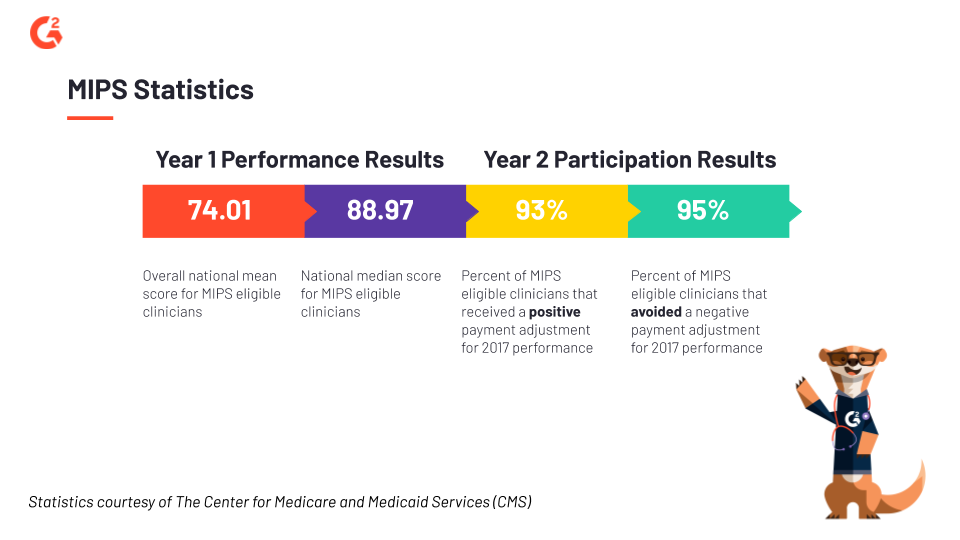

The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the most recent iteration of tying health care organizations’ reporting on the quality of their care processes and health outcomes to financial incentives and organizational reputation. We are in Year 3 of the MIPS program and on the heels of Year 1’s Medicare reimbursements (2017). (The 2018 MIPS feedback report will be released by The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mid-2019.)

In the columns following this introductory one, I will delve further into how MIPS scores and other forms of health care data impact and can be leveraged by medical providers for operational and patient experience optimization. Setting the stage with a breakdown of what MIPS and its scores are, poking at its missteps alongside its successes, will help set the stage on how medical-focused software can help providers do their jobs better.

What is MIPS?

MIPS makes up one of the two value-based payment programs of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA); Alternative Payment Model (APM) is the second of the two programs. MIPS was rolled out in 2017 in an effort to recognize and incentivize the growth and efforts of physicians and providers. MIPS scores are long-lasting and have already demonstrated their impact on medical performance reporting, patient loyalty, referrals, and the overall health of hospitals, clinics, and other health care organizations.

MIPS is an outstanding program because of its public reporting. CMS publishes data of all eligible clinicians onto its Physician Compare website to disclose delivery of care performance to the public. Posting such information on a public website impacts the dynamic between provider and patient. Consumer feedback has already played a large role in the retail and customer service space; now the public can see, disseminate, and leverage how well a potential clinician performs, according to a specific set of government standards.

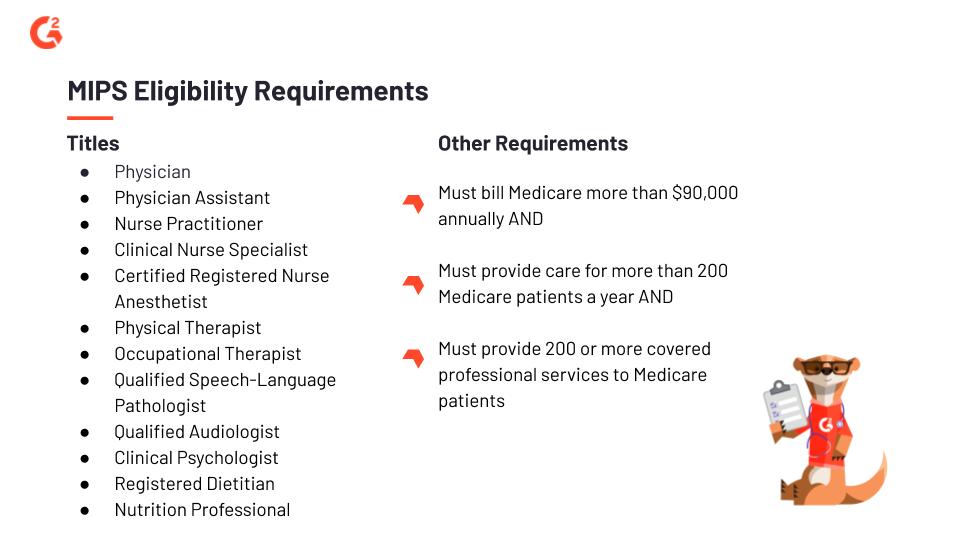

There is a caveat: MIPS does not include all providers. There are, as with most things, eligibility requirements. Those requirements change as the MIPS program evolves, allowing more physician and provider types to opt into MIPS.

Who is eligible for MIPS?

Those who do not fulfill the following requirements cannot opt into the MIPS program, missing out on the long-term benefits of publicly disclosed scores. Notably, if you or your practice is eligible, and do not meet the MIPS’ score threshold, you will observe a negative impact on your reach, reputation, and financial allocation.

Important dates for MIPS in 2019

-

-

-

- Jan. 1 - Dec. 31, 2019: The MIPS 2019 performance period

- March 31, 2020: The deadline to submit MIPS 2019 data

- July 2020: The date when eligible clinicians receive MIPS 2019 performance feedback from CMS

- Jan. 1, 2021: The date when MIPS payment adjustments are applied to each claim

-

-

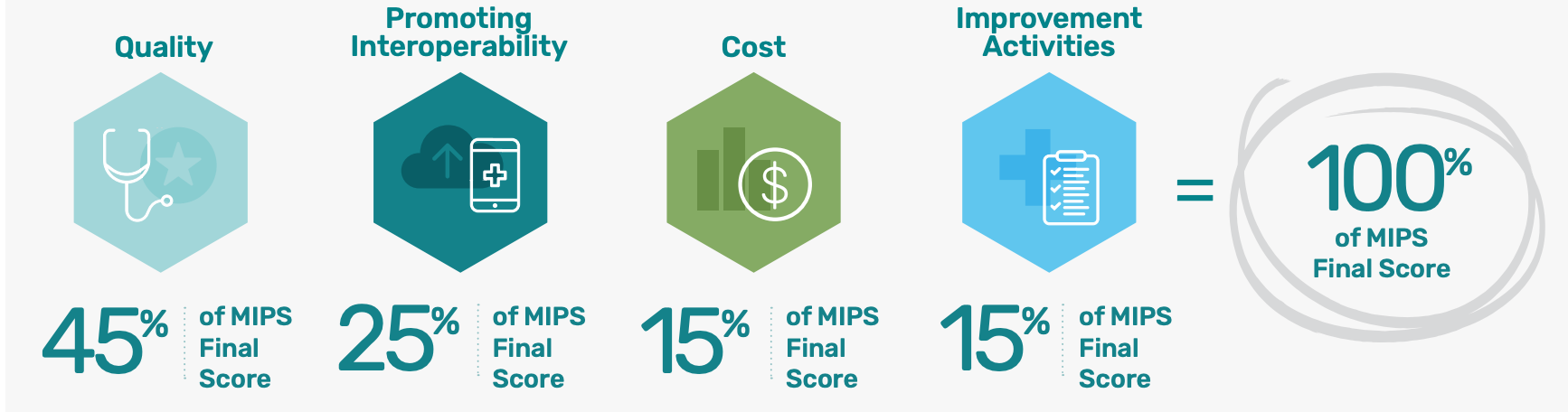

How is the MIPS score calculated?

The final MIPS composite performance score (CPS) that CMS provides to health care organizations determines the payment adjustment they will receive the following fiscal year.

Image courtesy of CMS Quality Payment Program

Image courtesy of CMS Quality Payment Program

An organization’s MIPS score is composed of four performance categories:

- Quality — 45% of total score

- CMS, medical professionals, and stakeholder groups create myriad performance measures that rank and report on the quality of care delivered to patients. If an organization is exempt from PI, Quality accounts for 70% of the score. If an organization’s Cost cannot be calculated, Quality accounts for 60% of the score.

- This category has been renamed from “Advancing Care Information,” to focus on patient engagement and education, and the use of technology to facilitate clinical communication and collaboration. Four objectives make up the scoring: e-prescribing, provider-to-patient exchange, health information exchange (HIE), and public health and clinical data exchange.

- IA is a new category that conducts inventory of an organization’s care coordination and patient engagement activities. IA takes into consideration the amount of effort an organization puts into improving overall care processes and access.

- CMS calculates Cost by comparing the cost measures of a health care organization against benchmarks, and gauging Medicare claims against utilization efforts. Cost has only been counted towards the final MIPS score since 2018.

The four categories are weighted, then added together to generate a CPS. Bonus points may apply based on factors like size and setting of a medical practice.

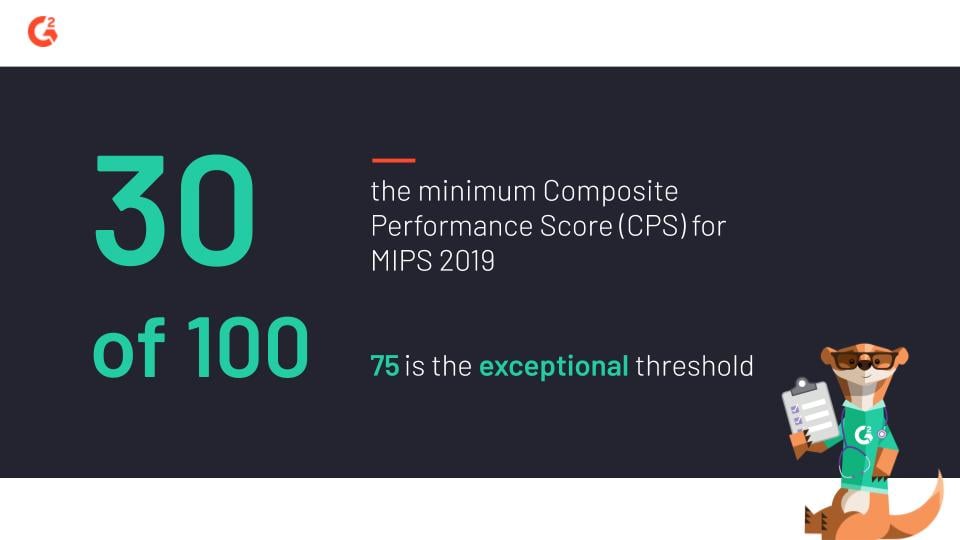

The “best” or “bottom” performing providers are identified based on where their scores fall on MIPS CPS bell curve. Each year, CMS sets a minimum and exceptional performance threshold; in addition to that minimum threshold number determining the positive or negative performance of a provider, it acts as a net-zero, neutral gateway. A provider who meets that exact threshold number sees no penalty—and no incentive—on its Medicare reimbursement payment.

Providers who exceed the threshold (dubbed “high performers”) receive a positive payment adjustment (up to 7% in 2019), while providers who fall short of the threshold (dubbed “low performers”) receive a negative adjustment (as low as 7% in 2019). Providers who exceed the exceptional performance threshold number receive an extra bonus, proportional to the amount their score exceeds that number. The adjustments come at the expense of the low performers.

In 2019, Medicare has set the CPS minimum threshold to 30 out of 100. The exceptional threshold is 75. In 2018, the minimum threshold had been set to 15, and the exceptional threshold was 70. In 2017, the minimum threshold had been set to 3, and the exceptional threshold was 70.

CMS is still adjusting the benchmarks and requirements when it comes to equitably comparing and scoring health care providers against each other. The rising minimum threshold is because MIPS must raise the level of competition between providers and health care organizations yearly. When the level of competition increases, the more impact MIPS scores have on the amount of financial reimbursements an organization receives and on the reputation of a medical practice.

Preparing your 2019 MIPS submission

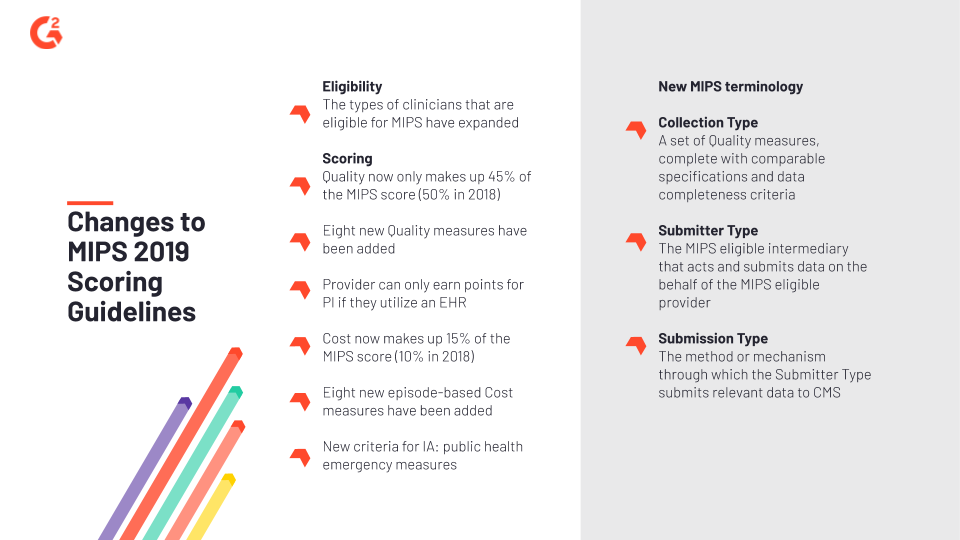

The deadline to submit 2019 MIPS data is around the corner, March 2020. We’re more than halfway through the 2019 MIPS reporting year, so it would behoove you to take note of some of the program guidelines that have changed since 2018:

The consequences of MIPS

There are a few issues with MIPS. MACRA touts MIPS exclusions as the least burdensome to practices and providers who shouldn’t be penalized for size and resources. However, they don’t give solo or small-group clinicians a chance to compete. Providers that bill higher have the ability to opt out (with monetary penalty), yet providers who don’t provide care to 200-plus Medicaid patients or deliver 200-plus covered Medicaid services are left out in the cold?

The impact of MIPS is clear: Health Affairs, a health policy and reform publication, bluntly referenced medical journal Annals of Internal Medicine’s estimate that “MIPS can cause up to a 46% spread in clinician payment rates over the next 5 years. Comparatively lower reimbursement lessens excluded clinicians’ ability to improve care delivery.” MIPS scores can either dissuade or legitimize perceptions about a provider.

When the minimum threshold score is as low as 15, and smaller organizations can leverage the bonus points awarded to small practices, there’s no real reason why they cannot participate. If MACRA wants to help eligible clinicians remain fiscally efficient while still providing a higher quality of care, they should not be allowed to exclude providers that do not bill a certain number of services or patients. The size of an organization doesn’t reflect the quality of care delivered or the improvement and engagement measures implemented.

The Catch-22 is obvious here: If a small practice isn’t allowed to earn substantial Medicaid payment increases on the sole basis that they’ll be unfairly compared to bigger practices, how can they improve their services to get to the same level without the proper funding or support? After all, MIPS scores are publicly reported; they follow individual clinicians around. What kind of impact will that have on both the hiring and patient front? Prospective medical staff and payers, as well as informed patients, will gravitate toward high MIPS performing providers.

Amazon customer reviews, Google listings, Angie’s List, Yelp, Glassdoor, TripAdvisor, G2 — customer feedback and reviews fuel consumer habits. Consumers are no longer only swayed by guerilla marketing and flashy advertising; personalization and third-party vouching are powerful forces when convincing anyone to buy into any product. People no longer wonder if they are the only ones receiving a good or bad experience; review sites for all kinds of industries exist, to help people make financial decisions.

The health care industry is no different.

The public’s perception of a medical practice is crucial to its stability. No matter the level of care and expertise a non-MIPS scoring provider offers, its absence on the MIPS score database casts an unfavorable light on the entire organization.

¿Quieres aprender más sobre Software de atención médica? Explora los productos de Cuidado de la salud.

Final thoughts

In theory, the zero-sum concept of MIPS is equitable and logical. In practice, though, MIPS makes health care a game. The winner succeeds at the expense of the loser, low-performing providers are punished for factors that are out of their control (i.e., volatile patients’ perception of their services), and the number of high-performing providers can stretch the incentivizing reimbursement pool too thin.

The silver lining here is that MIPS is only in its third year. There is a two-year span of time between reporting and feedback, which offers providers a chance to improve their scores the right way: slowly, over time, and with legitimacy. The two-year window gives providers time to breathe and get a full grasp of the implications and impact of MIPS; they can wrap their minds around the financial mechanics of MIPS and update their strategic planning.

Because MIPS is in its infancy, the hurdles and issues that have cropped up have resulted in changes to scoring, eligibility, and categorization. There’s a chance that future feedback is taken seriously by CMS, resulting in a more gradual, thorough, and fair transition to MIPS across the board.

The implementation of MIPS, despite some pushback from health care professionals, is ultimately a good thing. The health care industry must transition smoothly to value-based reimbursement and care models. While hospital administrators may put too much focus on MIPS scores, the trickle-down benefits are still good. For example, Medicaid reimbursements to the provider translates into bonuses to the medical staff. In addition, patient interactivity and positive health outcomes have become less buzzword-y jargon and more legitimate contributing forces to overall changes in the health care industry.

Jasmine Lee

Jasmine is a former Senior Market Research Analyst at G2. Prior to G2, she worked in the nonprofit sector and contributed to a handful of online entertainment and pop culture publications.